This is part 3 of my blog posts to accompany my ADS2023 Poster.

Waughter? Worder? Wooder?

In my first post, I talked about the timeline of when Philadelphians came to realize there was something distinctive about the way we say water, and the use of <wooder> in print. In my second post, I modelled the timeline of when Philadelphians started saying [wʊɾɚ], which seems to have been in variation with [wɔɾɚ] and [wɔɹɾɚ] for people born across the 20th century. Now there’s just the question of why any of this happened at all.

Story 1: [wɔɾɚ] raising

One possibility is that changes in the pronunciation of /ɔ/ just naturally shifted the vowel’s pronunciation in water in particular. If you look at the <ɔ> symbol on an IPA chart, you’d probably describe it as a mid to low back vowel. However, /ɔ/ is pretty significantly raised in Philly so that for many speakers its more like a high back vowel.

In fact, this is essentially the story we told in 100 Years of Sound Change. (“/oh/” and “open-o” are how we referred to this vowel).

The parallel back vowel is /oh/ in long open-o words talk, lost, off, and so on. Here the social stereotype is firmly fixed on one word, water, pronounced with a high back nucleus.

Labov, Rosenfelder, and Fruehwald (2013)

In a lot of ways this story makes sense, since not only is /ɔ/ very high in Philadelphia, but with it coming immediately after a /w/, the coarticulatory effect could pull it even higher to [ʊ].

Some shortcomings

A shortcoming for me about this story is that there are other words with a /wɔ/ sequence that haven’t shifted to [wʊ]. For example, wall [wɔɫ] is very distinct from wool [wʊɫ] for me. Similarly, none of walk, Waldo, walnut, Walter, waltz have [ʊ] in them.

This is a classic kind of problem/debate in the study of sound change. Is it exceptionless? Does it happen all at once, or does it move word by word?1 This could be an example of “lexical diffusion”, where for some reason or another, change from [ɔ] ➡️ [ʊ] happened in just one word, water, and not in any of the other words that are similar.

Story 2: Passing through Worder.

Another possibility here that recently occurred to me is that maybe the [wɔɹɾɚ] tokens I found in the PNC aren’t just some third variant in the mix, but are actually evidence of how water moved from [ɔ] to [ʊ]. But it has a few steps to it.

r-dissimilation

Unlike a lot of eastern seaboard cities in North America, like Boston, New York City and Charleston, Philadelphia has always been an /r/ pronouncing city. Where in Boston and NYC they might drop the /r/ in park [phaːk] and car [khaː], Philly has always pronounced that /r/: [phɒɹk] and [khɒɹ].2

The one exception to this rule is when there is more than one /r/ in the word, and if one of those /r/s is dropable, people are likely to drop it (Ellis, Groff, and Mead 2006). This tendency is maybe most notable in the name of a nearby suburb and college “Swarthmore”, which is usually pronounced [swɑθ.mɔɹ]. In fact, Swarthmore College recently capitalized on this variation in dueling billboards.3

But, this /r/ dissimilation isn’t restricted to just the word “Swarthmore.” The first /r/ is usually dropped in words like “quarter” or “corner”.

Reinterpretation

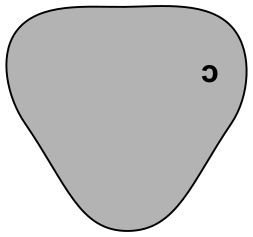

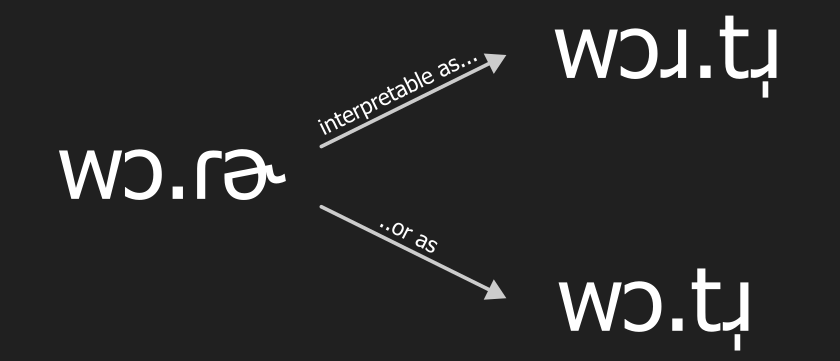

I think this /r/ dissimilation is what got “worder” in the door, which I’ll try to illustrate with an example. Let’s say you’re in Philadelphia and from Philadelphia, and some shows you this coin and says “Here’s a [kʰwɔ.ɾɚ].”

There are two possible ways you could decide to interpret the underlying form of this word. The first would be to take into account /r/ dissimulation, and stick the /r/ back in, for a /kʰwɔɹ.tɹ̩/ representation. The other would be to not take into account /r/ dissimilation, and decided on a /kʰwɔ.tɹ̩/representation.

Now, let’s just take off the [kʰ] at the beginning, and we have a remarkably similar kind of interpretation pathways for water!

Merger

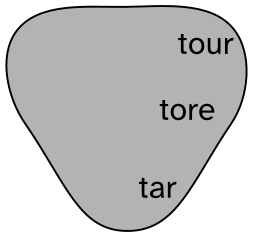

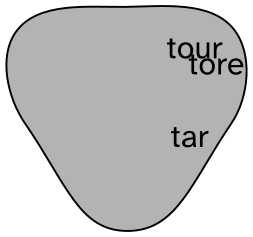

So, not only is the /wɔɹ.tɹ̩/ reinterpretation plausible, I heard a lot of [wɔɹɾɚ] when I was coding the data. The next thing to know about these vowels in Philly is that the vowels /ɔɹ/ (as in tore) and /uɹ/ tour have merged to a high back position. Perhaps the most noticeable aspect of this merger is that it’s dragged /aɹ/, as in tar, to a much higher and rounded position in Philly than many other varieties.

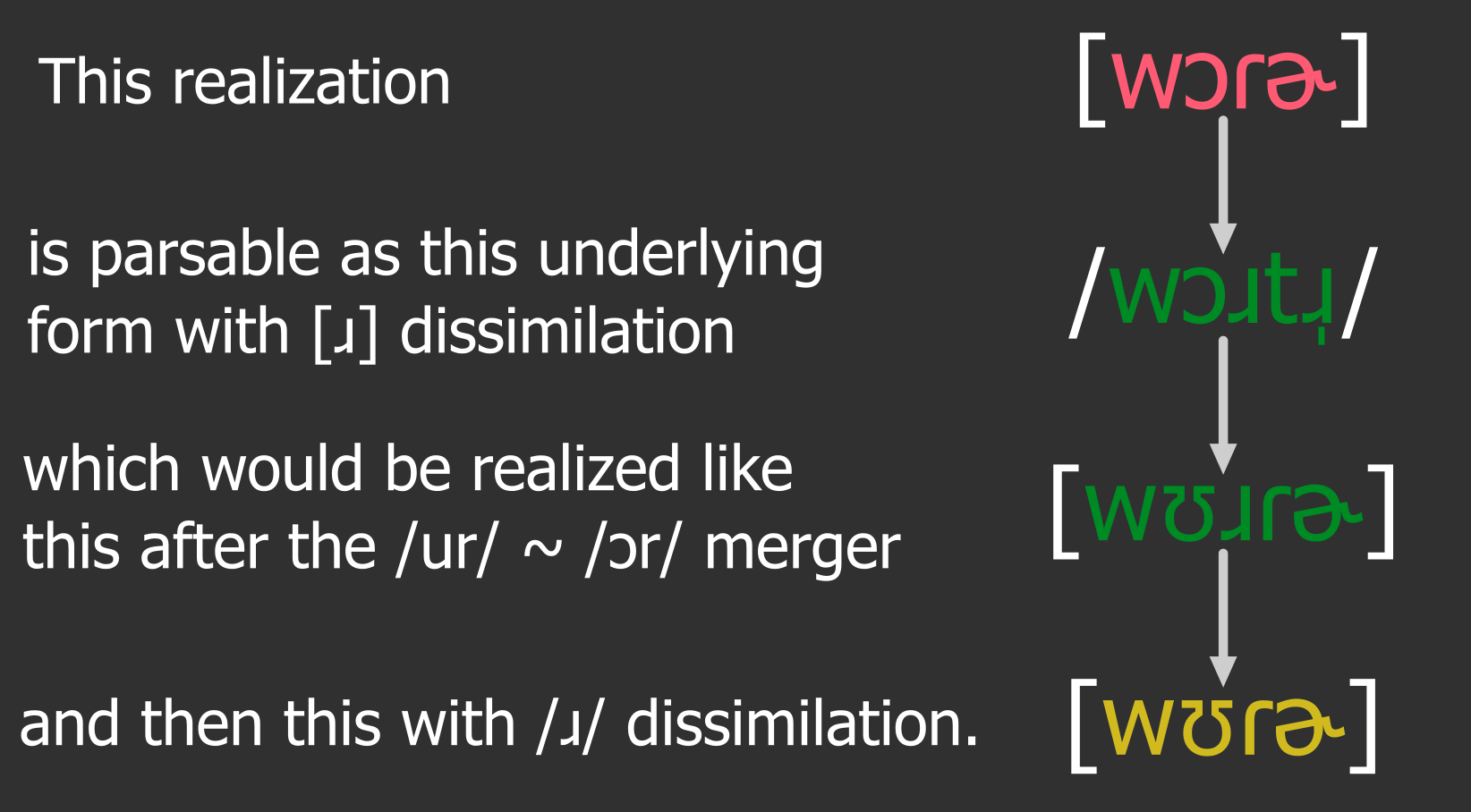

If people were inserting an /ɹ/ into the middle of water, it would belong to this /ɔɹ/ vowel, and we would expect it to be merged into /uɹ/.

So, once you’ve put an /ɹ/ into the middle of water and merged it with /uɹ/, what do you get if you then do /r/ dissimilation on that?

Wooder!

Shortcomings

So, a shortcoming of this story about how we got “wooder” is that it could seem a little convoluted. Like we decided to just stick an /ɹ/ in just to delete it later, and voilà! Wooder!

Benefits

On the other hand, there are a bunch of [wɔɹɾɚ] tokens in the Philadelphia Neighborhood Corpus. It also would account for why non of the other /wɔ/ words had this shift to [ʊ]. It also captures a but of what’s going on with daughter as satirized by the SNL skit Murder Durder.

Which story is the right one?

I’d say I need to do a bit more work, looking at the acoustic data more closely, looking at how individuals vary, as well as looking at daughter and the other /ɔɹ/ words that both have and don’t have /r/ dissimilation to really get closer to settling the issue.

But I think the way you react to each account could shed a little light on the kind of linguistic analyses you prefer. I really like Story 2. All the pieces that make it work are happening and have been described already, so I didn’t need to describe any new phenomenon to get “water” to turn into “wooder”. It just got pulled up in the interplay of different sound changes. It looks like a beautiful pattern, to me.

However, maybe Story 2 looks overwrought to you. “Words just do things sometimes!” you might say. “The /ɔ/ was rising, and there’s a /w/ right there!” And you know what, fair enough! That was my own analysis until about a year ago as well.

The good news is that Story 2 has piqued my interest, which means I’m going to be digging into this more in the near future. And maybe as I go I’ll find the “passage through worder” account unsupported, but for right now it seems really plausible to me!

References

Footnotes

Labov (1981), Bybee (2002), Phillips (2006), Fruehwald (2007), and many many others↩︎

I’ll come back to that different vowel in a sec.↩︎

-

↩︎Have you seen the new signs at the (SEPTA?) train station? 👀 pic.twitter.com/3DYfiGcRPs

— Swarthmore College ((swarthmore?)) August 26, 2022

Reuse

Citation

@online{fruehwald2023,

author = {Fruehwald, Josef and Fruehwald, Josef},

title = {Rising {Wooders:} {Part} 3},

series = {Væl Space},

date = {2023-01-04},

url = {https://jofrhwld.github.io/blog/posts/2023/01/2023-01-04_wooder3/},

doi = {10.59350/fz4q8-sdm65},

langid = {en}

}